Enduring Hardships of the Plantation System Before WWII

Japanese and other ethnic groups faced difficult working and living conditions.

Japanese workers, Kilauea Sugar Plantation, Kauai (ca. 1912). (Photo: Hawaiian Historical Society, H.W. Thomas Album)

In the late 19th century, major sugar corporations in Hawaii known as the Big Five were powerful politically and economically. As a result, Hawaii at the time functioned more as an oligarchy than a democracy. Japanese immigrated to Hawaii in large numbers beginning in the late 1800’s, seeking a better life for themselves and their families, fulfilling the need for cheap labor to work on the sugar plantations.

These workers, mostly single farmers from poor families, came to Hawaii with expectations of a wonderful new life, hoping to make money and return to Japan as wealthy men.

After arriving, however, they found the plantation system to be oppressive — long days of hard labor for minimal pay, overcrowded barracks, fines for misconduct and at times physical violence; their lives were strictly controlled by the plantation system.

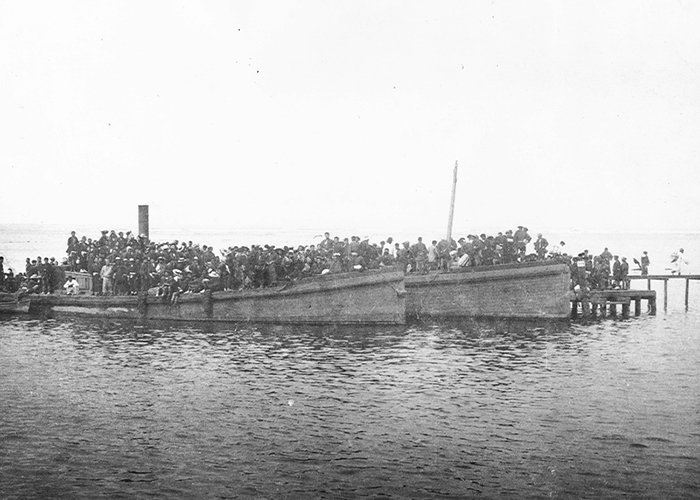

Japanese contract workers disembarking off shuttle boats in Honolulu Harbor (1893). (Photo: Hawaii State Archives)

Issei women working on a plantation (date unknown). (Photo: Hawaii State Archives)

As the first generation of Nikkei (overseas Japanese) completed their contracts, some left the plantations to earn more money and have a better life. They established small businesses that sold goods or provided services to a growing Nikkei community. Issei (first generation Japanese) who remained on the plantations fought for better wages and treatment and participated in labor strikes.

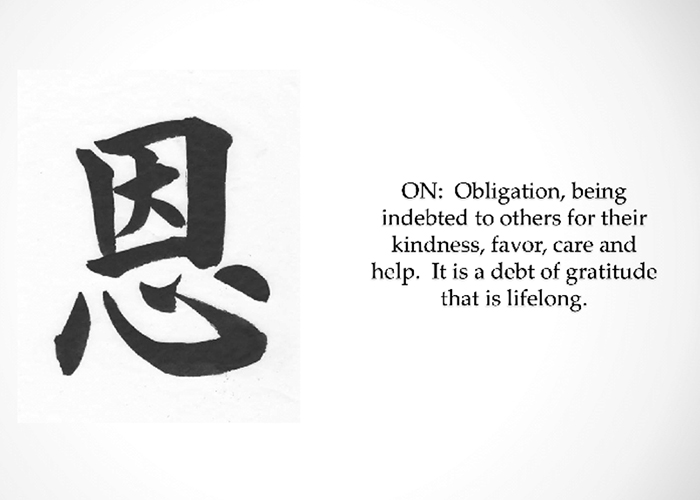

The Issei instilled Japanese cultural values such as Haji (never bring shame to the family), Gaman (maintaining one’s dignity and honor), On (lifelong debt of gratitude), and Ganbari (persistence and steadfastness) in the Nisei (second generation Japanese). These values would serve the Nisei well when they went off to war to prove their loyalty as Americans.

The Nisei were taught Japanese customs but were raised as Americans — however, they were still treated as subordinated citizens in the land of their birth. They found themselves closely associating with and learning the culture of native Hawaiians as well as those of the Chinese, Portuguese, Filipinos and Koreans who had also been brought to Hawaii to work on the plantations. The Japanese culture became a part of the blended multi-ethnic fabric of Hawaii. This strong sense of collaboration later proved to be beneficial in shaping Hawaii after the war.

Calligraphy by Mrs. Minako Kamuro